AWARENESS

The Dimensions of Change

When the voyager probe emerged from behind Saturn during its flyby of the planet in 1981 it appeared that the camera platform had malfunctioned. The once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to capture images of Uranus and Neptune on this unique mission, that was only made possible because of the way the planets had lined up during a small launch window, was in jeopardy. It took ingenuity and perseverance to avert a potential disaster. The analogy here is that there will be a time in your life where things don’t work out the way you want them to and making the changes you need to correct the problem can be challenging. In some cases, the timing can be critical and you may find yourself with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to make a meaningful change. In this article, I want to introduce you to the most important aspects of making a change, which I refer to as the dimensions of change.

A lot of change happens as a result of things that change in your working environment or personal life where the change is external and outside of your control. You have a choice in how you respond to these changes, and your ability to adapt is a measure of your resilience. Another source of change may be driven by internal factors, where there is a change in your perception or interpretation of something, your belief about something or the relative importance of your priorities. When you want to make a change happen [take action to initiate change] and this is driven from an internal locus of control, there are eight dimensions you can focus on. These dimensions are the attributes of change that need attention and will enable you to change your life for the better. This is how to make a change, any change, and essentially how to implement change in your life or work.

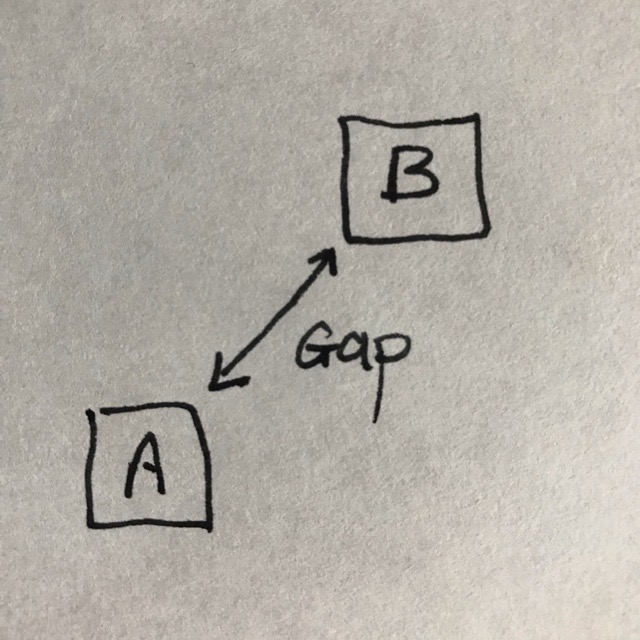

1. Identify the gap

“Mind the gap” is a constant warning you will hear on London underground trains. The gap, in this case, is the difference between where you are and where you want to be, or what something is and what you’d prefer it to be. In the graphic in this section ‘A’ represents your current situation, and ‘B’ represents your change objective. The first step in any change process is to identify or acknowledge this gap.

Around the time I started studying an MBA at the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business (GSB) I experienced a bit of an existential crises in my career. I had managed to escape the fires of hell in the steel industry and the tiny little industrial town in the middle of nowhere, after that, and I was working for a well known Oil and Gas company in what I considered to be the most beautiful city in the world, but a new problem had emerged from my subconsciousness. My job entailed supporting business investments in future refinery capacity and fuel quality and although it was exactly what I wanted to do and was aligned with everything I had managed to achieve with the changes following on from my four month sabbatical in North America, I realised that it meant that I was contributing to the global source of carbon emissions to atmosphere, which was at the heart of the climate change problem. As someone who had loved nature and treasured biodiversity all my life I started questioning the ethics and my personal responsibility in contributing to this climate change problem. I realised that I could potentially use my talents and skills to work on the solution. I was essentially working in the energy industry and I knew the best approach would be to work on renewable energy projects as a form of carbon emission mitigation. The gap was clear to me, I wanted to switch my career role from carbon emissions related activities to renewable energy. So I started looking for a solution to this problem.

Awareness that there is a desire for change or the potential for change, is the first essential step in making change happen.

At this stage, it is important to define as much as you can about why there is a gap. What makes your current situation unpalatable and undesirable and then get into the details about what it is that you want to change. Focus on your interests and values and reassess your beliefs and expectations. Go deep on this exercise, it will help you figure out how much tolerance you are willing to accept at a later stage. This is where you create your definition of success.

2. Potential Difference

For any change to happen there needs to be a tension between two states of existence representing a potential difference in energy levels that acts as the driving force for change. Analogies would be an electric battery, the pressure difference of water in a hosepipe, or a weight suspended at height in a gravity field.

The way to ‘measure’ the potential difference for change is to evaluate it qualitatively by understanding why your current situation or state (‘A’) is undesirable and why the preferred future position or state (‘B’) is more desirable or preferable.

3. Commitment Change Vector

Your attitude towards any change is going to influence your commitment to addressing that change. This is driven by the importance you place on the need for change, your perception and belief that the change is possible, and how much effort is going to be required to make it happen. The more important the issue is to you the more likely you are going to be committed to doing something about it. Think of it as a vector in the direction of change with the magnitude being your commitment to make that change, and this is proportional to how important it is to you, how much belief you have that the change can be achieved, and how much effort you think would be needed to make the change happen. Your motivation is going to be directly proportional to your commitment change vector.

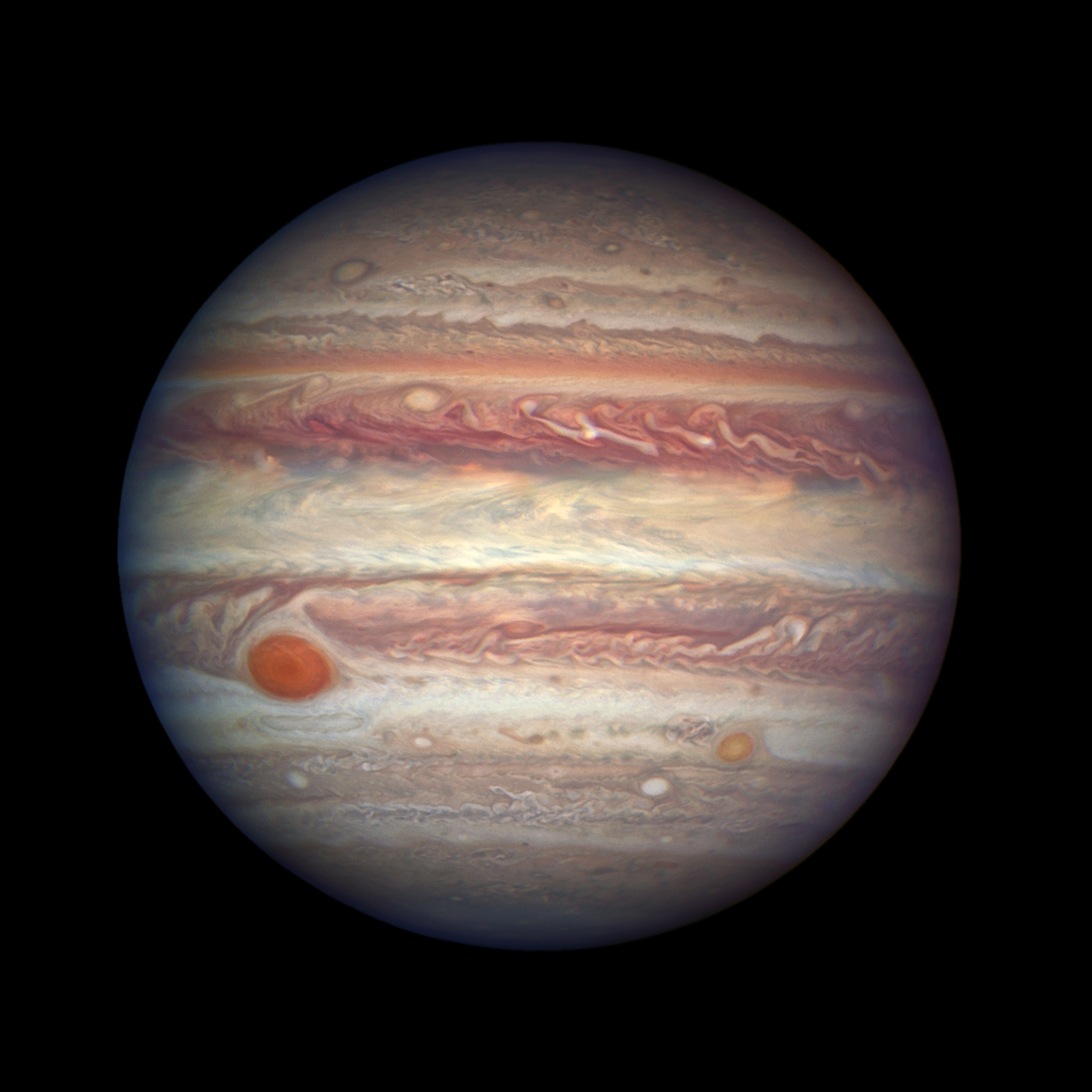

4. Conservation of Momentum

When I was five years old I looked up into the night sky one evening and asked my parents what the stars were. They told me that they were ‘stars, of course’. But I wasn’t happy with the answer. I knew they were called stars but I wanted to know exactly what they were. So my Dad told me they were “balls of burning gas”. Then I wanted to know what ‘gas’ was and why did it burn. The questions didn’t stop. I was born with an infinite reservoir of curiosity. When I was six or seven years old I saw an image of Jupiter and asked my mother, who was with me in a book store at the time, what it was. It was the best telescope image humanity had of Jupiter and it was the destination of the voyager planetary exploration probe that had just been launched. When she told me it was a near-by planet I was shocked. How was it possible that something I thought was just a bright star and a tiny little point of light could actually look like that if you got close enough to it. These early discoveries lead me to have a particular fascination with space, astronomy and cosmology. I gravitated to maths and the sciences and it eventually lead me to engineering as a profession. So a lot of the analogies and metaphors I use to lean on are heavily influenced by ‘sciencey’ type concepts and topics and I make no excuses for being a bit nerdy in this respect.

Jupiter

Photograph by Hubble Space Telescope

I specifically like to use metaphors and analogies as a way to strengthen knowledge and insights because it’s the way we learn – through cross-linkages and association. My observation of the natural world has lead me to realise that there are some principles that appear to apply to multi-disciplinary applications and I think of them as being universal. These are my universal principles and they transcend a lot of the topics I am interested in. They are the universal principles of balance, relativity, and systems hierarchy. Added to these are the physics related principles of energy and momentum conservation.

The universal principle of the conservation of momentum is an observation about the nature of the universe we live in where a body with mass that is stationary will remain stationary until acted on by an external force. Similarly, a body of mass that is in motion will continue to move in the same direction unless acted on by an external force. The next dimension applies the conservation of momentum by noting that action is needed to make a change. There is no way you are going to make a change in your life or work role unless you take action. Action requires a decision, supported by sufficient motivation and commitment. Having made a decision to act, the action needs to be sustained and this is best achieved by taking consistent action supported by new habits that drive progress along the path of change.

There is a whole body of academic research focused on decision theory and there are a few good resources on how to make a decision, specifically this MindTools article that describes an approach to follow when making a decision involving a relatively high degree of complexity.

The first actions you take may feel like the hardest because there is so much stationary momentum to overcome. To get moving and to make the change you are looking for, you might need a change catalyst. Always remember that a journey of a thousand miles starts with one step.

Exactly what actions you take, what strategy you apply and how you make the change happen is something I address in another article using the analogy of building rockets [add link when ready].

5. Change Catalyst

A catalyst is a substance that increases the rate of a chemical reaction while not transforming in any way as a result. Generally, the way a catalyst works is that it helps to lower the activation energy of the reaction, and quite often it facilitates the path of the reaction.

My Change Catalyst Mandala

Brett Dawson

Using this analogy when it comes to change, I consider a change catalyst to be something that lowers the activation energy to make a change happen and also helps to lower the friction resisting the progress of change. In its simplest form, a change catalyst is something that makes the viability of the ‘change destination’ or the ‘change path’ easier. It facilitates and enables the change. A change catalyst may take on many different shapes and forms. It may be an inspiring article you read, a story you hear, a person you meet, or a new idea or perspective you get that helps to make you believe the destination and path are possible. A change catalyst not only inspires you to take action but makes it easier to do so. It is something or someone that changes your mindset, attitude and commitment to change, your appetite for risk, and collectively empowers you to take action. A change catalyst can also help overcome or circumnavigate blockages.

6. Tolerance and Agility

Accept that the destination is not absolute. Have some tolerance for a bit of variability in the final shape and form of your goal and objective. The destination ‘B’ should not be too prescriptive. ‘Close enough but not quite’ might be good enough. However, ‘good enough’ shouldn’t be a compromise. It should be an acceptable variation in what you are really looking for.

The best way to understand how much tolerance you are prepared to accept for a solution that is ‘good enough’ is to be clear on what it is you want to change and why. You will have explored this in the first dimension of change when you were identifying the gap. It is wise to revisit your feelings and thoughts about the gap you defined in the first dimension. Treat it as an iterative process.

Similarly, accepting that there are many different potential paths to achieving your change objective enables you to be agile and flexible. Outcome tolerance and agility in finding a path to get there are key success factors to effective change.

‘Good enough’ shouldn’t be a compromise. It should be an acceptable variation in what you are really looking for.

7. Friction

Where there is motion there will be friction. Expect it. Plan for it. Be resilient towards it. Friction is proportional to the speed of travel or the rate of change. The thing that intimidates most people about change is the momentum of change. Momentum is speed multiplied by mass, and change momentum is the speed of change multiplied by the size of that change. Both of these attributes increase the resistance most people feel towards change, be it individually or in groups. If you’re a systems thinker, like me, you will also realise that dynamic change will emerge from system dynamics and this will make it feel like the goalposts are constantly moving. This will add to your perception of the friction involved.

Change requires restructuring and this involves tearing some things down and rebuilding new structures, literally and figuratively. Existing systems and ways of doing things, and established habits and routines are all the things that will add resistance to the change you are trying to implement. Chances are good that you will be heading into new territory: physically, intellectually and emotionally. This will feel uncomfortable and will require you to learn new things. You will need to learn to find your way around new locations. You will need to acquire new knowledge and insights. You will need to learn to deal with new emotions. Your ability to learn and attitude towards learning is foundational to your ability to implement change. It is the cornerstone of resilience and dictates how well you will be able to adapt, regardless of what the circumstances are and how large or ambitious your challenge is.

There will be times when you feel stuck. It may feel that the path of change is blocked. This is when the friction you are experiencing is preventing you from making further progress. There are many potential reasons for this and sometimes they aren’t always visible or apparent to you.

One potential reason could be that you have other competing priorities, some of which may be subconscious. Another reason could be associated with the complexity of the changes you are considering, especially where there are multiple factors of consideration. These factors can be difficult to separate especially when the change you would like to implement results in additional undesirable consequences (which may or may not be directly related to what you are trying to change). A classic example here would be where a change in your work role requires you to move to a new city but you currently live close to your elderly relatives, who need your support, which makes these two unrelated needs incompatible. In this situation, you would need to continue to explore alternative options looking for a viable solution while applying tolerance to the nature of the final solution.

Another form of interdependency may be that the change you would like to make happen is dependent on a solution that involves collaboration with other people. Here your skills of relationship building and persuasion are going to be important. In fact, most of the change you may want to make happen is probably going to require you to collaborate with other people in one way or another.

One of the skills of managing personal change is to manage the change momentum and the best way to do this is to take small achievable steps wherever you can. Once you’ve taken that first step on your journey of a thousand miles, take the next single step. And then the next one. If you find it difficult to take a step or the path seems to be blocked then stop and analyse the issue. Treat it as a problem that needs to be solved. Be open-minded and switch to learning mode. Be patient and work the problem. Stay focussed. Find inspiration to keep you working on it. Be tenacious and persevere. Find different types of change catalysts to help you and if all else fails, ask for help. Asking for help is smart because it will reduce the time it takes you to figure it out yourself.

The universal principle of balance is my observation that there are advantages and disadvantages to everything.

8. Balance

The universal principle of balance is my observation that there are advantages and disadvantages to everything. The aphorism that comes to mind is that one man’s nightmare is another man’s dream. Disasters and opportunities are intertwined depending on one’s perspective, objective, goals, aspirations, and vested interests. The universal principle of relativity influences perspective, and is probably the most important tool in your ‘how to make a change’ toolbox.

As much as it is important to be tenacious and to persevere to be able to overcome the friction against change, there is also a need to apply a bit of tolerance to the final solution. How close is ‘good enough’? It’s a relative interpretation and will be different for each person. The only way to figure out how much tolerance is acceptable to you is to dig deep into the details of your definition of success in the first dimension when you identified the gap.

Your challenge is to find the point of balance between perseverance and your tolerance for the final outcome. The nature of a balance point is that it is a state of equilibrium where you will experience tension because you will feel pulled in two different directions. It might even feel as if you have two incompatible and conflicting thoughts or requirements. It’s tempting to think of it as been stuck in a dilemma, when in fact, it is a healthy point of equilibrium. The good news is that you get to decide where that equilibrium point is. There is no right answer, there is only what is right for you. Sometimes, especially if you are scientifically minded and you’ve been trained to optimise, minimise or maximise things, it is tempting to think that there must be a ‘right’ or best answer. It’s tempting to think that there must be one perfect answer, one true global maximum. However, the practical truth is that it’s more of a local specific solution, that works for you.

It may be tempting to continue looking for another solution, hoping that it might be better than the last option you considered. It’s a bit like the modern dating dilemma where there are so many choices that it’s tempting to think that there must be one perfect person out there for you. It’s tempting to forget that the universal principle of balance is looking over your shoulder with a wry smile waiting for you to discover that every choice has some inherent disadvantage or undesirable attribute. Your only ally or skill here is the freedom of choice in what you focus on. If you focus on the downside, that’s what you are going to see. Focus on the upside, and the world has the potential to be a bed of roses if you can tolerate a few thorns along the way.

There is a surprising paradox when it comes to choice. A study was conducted by Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper in 2000 (the jam study) and concluded that having too much choice reduces our ability to make a decision. So part of the skill of making a change is to find the balance in the number of choices you have along the way. If the change you are trying to make involves a choice amidst many options, then you need to find a way to cut those options down.

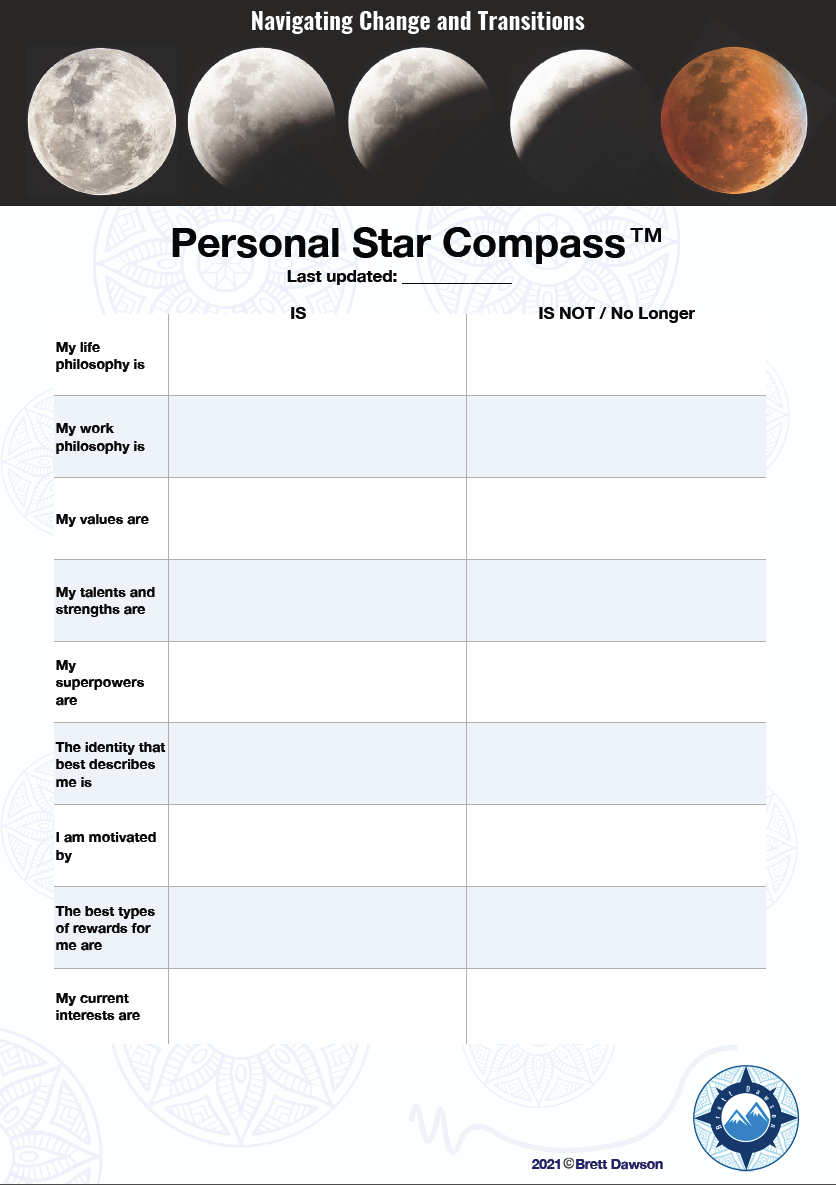

Download this template and use it to recalibrate your personal compass.

Conclusion

If you want to make a change, especially if that change is driven by an internal desire to make a change based on a preference you have for what something should be then these dimensions of change will guide you on how to make that change happen. The first step is to identify the gap between where you are and where you want to be. Then you need to find a way to increase the strength in the potential difference for that change. You should also look for ways to increase the strength of your commitment to the change vector. Determine what type of change catalyst you needed and then take action to build up momentum. Remember to be agile, tolerant and adaptable in selecting your final solution and the path to getting there. Expect friction along the way and find ways to overcome it. Finally, use the universal principle of balance to ensure that you find the point of balance between perseverance to make the change happen and your tolerance for the potential variability in the final outcome.