ESSENTIAL SKILLS

How to implement change with three simple ideas

The way to implement change in your life is to manipulate time and space. It’s an Einstein trick. You don’t need any maths or formulas to do this. Promise. Let me explain how this works…

Let’s start with something that Einstein is said to have said but didn’t actually say. Einstein did not say that insanity is doing the same thing over and over while expecting a different result. There are many quotes attributed to Einstein that are not true. That doesn’t change the fact that there is an essential nugget of deep wisdom in this statement. Reformulated, I would say that to implement any change in your life you need to start changing what you do and how you do it. The guiding principles that will empower you to do this might just rest on three fundamentally simple ideas. Let’s have a closer look at some of the metaphysical foundations of these simple and elegant truths.

The thing that I love about Einstein and one of the main reasons why he was such an extraordinary thinker is that he was interested in metaphysics, which is the branch of philosophy that deals with the first principles of things. In his many areas of interest, he was intrigued by the fundamental nature of time and space. Metaphysics includes grappling with the nature of being and how we know things. The very nature of philosophy is to question everything and it can get complicated and messy. But the transformation that great philosophers make is that they wade through the mess, get lost and then they reformulate how they think and distil simple truths out of the chaos. In the midst of that chaos, that everyone else can see and feels lost in, their simple truths suddenly look beautiful and elegant.

The other intriguing problem with philosophy is that it can be highly subjective and heavily influenced by contextual meaning. If I presented you with the three simple truths that drive effective personal change it might seem insignificant to you, or a bit weird and incomprehensible, or maybe so obvious that you might be wondering why I am placing so much emphasis on it. Let’s see. Tell me what your initial thoughts are in the comments section – here are the three relatively simple ideas:

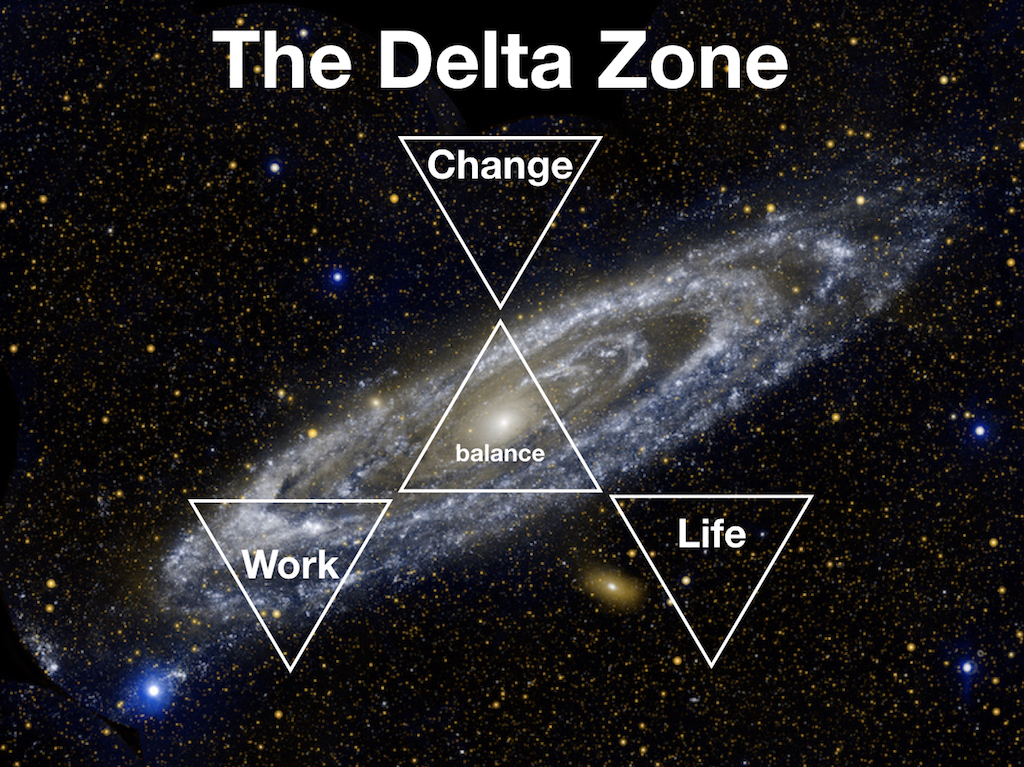

1. Change requires separation, which is best achieved in a dedicated ‘space’ and ‘time’ (I call this the Delta Zone)

2. Proactive change can only be achieved via two mechanisms: projects or routines.

3. Changes are subject to system dynamics.

Change requires separation, which is best achieved in a dedicated ‘space’ and ‘time’. I call this the Delta Zone.

The most impressive change in nature provides the first insight

The most impressive and radical change that you can find in nature is that of a moth or butterfly larva metamorphosising into a winged imago. The metamorphosis occurs inside a chrysalis or a cocoon, which is the dedicated space in which this miraculous transformation takes place. The insect’s lifecycle drives the timing and the transformation step can’t be rushed. During this transformation the pupa does not go out at night to find dinner, instead, it relies on food reserves built up during the larva feasting stage. The chrysalis provides protection from the environment because the pupa is not able to defend itself during the transformation process. All the pupa is capable of doing is transforming during this metamorphosis phase. It’s clear that this transformation requires a dedicated space and time.

The most difficult changes in life are…

The most stressful life events are all changes or transition events. These include significant losses like the death of a loved one, the breakup of a significant relationship, the loss of a job, the loss of good health with the onset of illness or injury, and a change in your living environment in the form of moving house. In many cases, several of these developments may occur at the same time due to the interrelated nature of the attachments in your life. The most notable attribute of these changes is a breakdown of how things used to work in the past. There is a change in routines, and a combination of changes to your environment, personal space and the people you spend time with. Quite often the thing that makes these changes difficult is the degree to which these changes impact everything else in your life. If you lose your job but you find another one soon afterwards then the duration of the change is short-lived and the impact is minimal. However, if the unemployment duration lasted a long time and this had a domino-type knock-on effect which resulted in you losing other things like your house and maybe even a significant relationship, then the magnitude of the change would be huge. Regardless of what changes occur, the two things that make change difficult are the size and the speed of the change. If you can find a way to contain the change, both in terms of time duration and scope of impact, then you will start to limit how difficult that change may feel. To do this you need to find a way to separate the change from other things in your life and the most effective way to do this is to wrap a container around it, both in time and space.

Work-life balance is a good starting point

The best example of a separation of activities that you may have in your life is the differentiation between work and home, where the popular notion of work-life balance probably plays a significant role in your perception and experience of quality of life. If you choose to spend more time in your work zone you can only do this at the expense of having less time in your non-work or ‘life-zone’. If you are forced to spend more time at work than you would like to then this will have a negative impact on your quality of life. It will probably impact your ability to rest and unwind. It will decrease the amount of time you can dedicate to non-work-related activities. If it impacts the amount of sleep you get and the quality of the sleep you get then it will impact your sleep-related hormone production, and that will quickly cascade into poor health during the day, which will impact both your work performance and life experience. The best way to avoid this snowball effect of increasing stress levels, poor health and degenerating quality of life are to maintain a rigorous boundary between your work and other life activities. Separating these two zones of your life in time and space is the best way to protect your productivity at work, and your enjoyment of life.

The COVID-19 breakdown of the work-life boundary

At the time I am writing this we are one year into the COVID-19 pandemic period and I am working from home while attempting to help my partner with homeschooling at times when they are trying to get some work done too. There is no separation between the work zone and the life zone while working from home and having the kids at home during school days. My kids are in primary school and still require additional support and supervision. As much as the teachers are doing their best to provide lessons online using various conferencing software applications, there is still a need to keep an eye on the kids to make sure they are attending their classes and doing their homework. At home, we need to review their homework, correct their mistakes and supplement by teaching new ideas and principles that they haven’t fully understood or grasped. My experience is that it is practically impossible to perform both homeschooling and work-related tasks at the same time. Especially when the work-related tasks require long periods of deep engagement in order to make meaningful progress. Several other parents I know have complained about the same problem – they feel that they are doing a very poor job on both fronts. In other words, nothing is getting the required time and attention that it deserves, and nothing is working well. I call this the pandemic-induced work-life entanglement problem.

Part of the reason for this problem is that the human brain is not very good at multi-tasking and pays a huge price for task switching. In Daniel Levitin’s book The Organized Mind he explains the metabolic costs of task switching, which include a large change in the blood oxygen level-dependent signal in the pre-frontal cortex and other parts of the brain indicating that glucose is being metabolized. He also cites a study which indicates that repeated task switching leads to anxiety and fatigue, and this anxiety raises levels of the stress hormone cortisol in the brain, which in turn can lead to aggressive and impulsive behaviours. The implications are simple, stick to one task and do it in an environment that limits distractions and you avoid all the inefficiencies of non-optimal brain function.

That’s an interesting statement, isn’t it? “Stick to one task and do it in an environment that limits distractions”. It sounds a bit like a chrysalis, doesn’t it?

The practical problems of time and space

If you sit back and reflect on this for a while you will realise that there is a very practical problem to effectively implementing changes in your life. Let’s say you wanted to make a change in your work zone, and let’s assume that you have a separation between work and life zones (i.e. you’re not trapped in the pandemic work-life entanglement problem). You can’t dedicate time and activities to make this change while you are at work without reneging on your work commitments or breaking your work contract commitments. Nor can you do this at home without ‘stealing’ from your home-related time and activities. So how do you do it? The most practical way is to ‘borrow time and space’ from either of those two zones (work and life or home) on a temporary basis while you do what you need to do to make the change.

Similarly, if you wanted to make a significant change in your life, like moving into a new home, you may need to do some research into what options are available and then take some time to view the new home. Once you’ve decided on a home you will dedicate some time to negotiating a rental agreement or securing a mortgage. You may be thinking this sounds bleeding obvious but you might be missing the nuance here. You are still taking time away from what you would normally be doing to focus your attention on this special change-related activity. Chances are you are blurring these activities into other times during your work day or your home time and there isn’t a clear differentiation between this activity and your other activities. It’s probably because this activity is a temporary disruption to your normal activities and when it’s complete you’ll get back to what you were doing before on a full-time basis. There’s no real separation between the time dedicated to these home-changing activities and your work or life zones. You probably see them as an integrated part of your work or life zones and just a temporary disruption. And let’s be sensible, you’re not a butterfly and it isn’t possible to put your life on hold and climb into a chrysalis while you engineer this change.

Thought experiment

So let’s look at this from a slightly different angle. Let’s do a thought experiment, which is something our friend, Albert Einstein, used to do to dig into the metaphysics of things like the speed of light when he was thinking about space and time. For this thought experiment, I want you to consider a scenario in which you found the perfect house and coincidently the people living in this house you want to move into happened to really like your house and wanted to move into your place, so you’d effectively be switching houses with them. Let’s say that both properties are rental properties and the agreed rental period ends on the same day, the end of the month. How do both of you get your furniture and belongings into the other house on the same day? You’ll both need to pack up everything in one day, move it over in a moving vehicle and unpack it all in one day. Depending on how much stuff you have this could be a logistical nightmare and result in a very long day. In the event that you cannot complete this task in one day, you may have to hire temporary storage space at another location. The important and subtle point to realise here is that all your belongings would have been temporarily housed in a temporary space (the moving vehicle or additional storage space) during the transition period. You will have had to have created a dedicated temporary structure in time and space in order to make the change possible. Change requires separation, which is best achieved in a dedicated ‘space’ and ‘time’. I call this the Delta Zone (where the greek letter Delta, is used in maths and science to denote changes in variables that are changeable). The butterfly’s chrysalis is a good metaphor for the Delta Zone, however, not all Delta Zones are physical. You can’t see an illness, but you can feel it or see its effects on someone else. When a relationship breaks down you see the change in behaviour before the person no longer spends time in close proximity to you. Before you move into a different house, you know the change is coming and the house you are in may start to feel different. The shifts can be quite subtle. The more overt you can make the physical manifestation of the transition space the easier it is to focus your time and attention on it. Similarly, you could also be more clear about your time boundaries around the change and transition. Looking for a new job or a new significant relationship should not take up every minute of the day that you are awake. It is much more effective to dedicate a time slot to it and put some containment around it.

A practical change strategy: The Delta Zone

This brings me to the most significant insight I have had about change and transitions, and that is to create a dedicated space for it, which should be separate from your work-life balance activities. There should be three zones: a work zone, a life zone and a dedicated change zone (the Delta Zone). In his book on Transitions, William Bridges uses the analogy of a home renovation to describe some of the challenges faced with change and transitions. When discussing changes in relationships one of his recommendations is to create temporary structures. In one scenario he suggests “it may involve agreements about how to allocate responsibilities until something more permanent can be devised.” He doesn’t place a lot of emphasis on this; it’s more of an observation about the temporary nature of transitions associated with change. However, I believe it should be one of the central tenants of managing change. Significant changes in our lives and work can be so profound and disruptive that they deserved to be treated with a dedicated focus. Just taking a change in your stride doesn’t give it the time and dedication that it deserves, especially if it is a significant or traumatic change. Change needs a dedicated ‘home’ in time and space – the Delta Zone. The way to leverage this is to consciously move what you are trying to change in either your work zone (e.g. find a new job or change your career trajectory) or your life zone (e.g. finding a new home, finding a new romantic partner or a friend) into the change zone. Having a dedicated change zone empowers you to dedicate the time, effort and energy required to implement the change you want to see in your life. It forces you to define what success looks like and what the criteria are for taking that area of focus out of the Delta Zone and reintegrating it into your ‘normal’ work-life balance side of life.

My experience with changes and transitions

Every single significant change that I have been through has been accompanied by some sort of time away from my normal routines and activities. The first career change I made involved a change in an industry where I moved from the iron and steel industry into the oil and gas industry. This was preceded by a working holiday, in which I left South Africa and went to London looking for new work activities. I call it a working holiday because I stayed in London for nearly three months and simply couldn’t afford to do that as a holiday, so I spent more than half the time working in non-engineering-related roles. Although I didn’t find full-time engineering work in the United Kingdom on that trip it did give me a very clear focus on the transition I was working through and helped me clarify what type of work I was willing to do. Five years later I was looking to make another change and this time I went on a four-month work sabbatical during which I spent three months touring and rock climbing in North America. A few years later I wanted to move to Cape Town and study for a part-time MBA at the Graduate School of Business. I could only do this if I could find work in Cape Town and so I used some of my leave to go on a work-hunting trip in Cape Town where I knocked on doors and networked with as many people as I could while looking for opportunities. Although I didn’t find work on that trip it helped me put routines in place that helped me identify an opportunity in Cape Town, which did enable me to relocate and complete the MBA at my first choice business school. About four years later I was presented with an opportunity to join the South African government as Director of Renewable Energy and instead of being too impulsive about it I took a day’s leave and walked up Table Mountain in Cape Town to reflect on it. There are several more examples but I don’t want to labour the point. Many of these temporary breaks have effectively been retreats without me even realising that I was taking a self-styled retreat.

When in doubt, take a retreat

Having realised how important this is I now proactively create retreats when I am dealing with a change or transition. A personal retreat can be anything from a few hours or a day to a week away.

How to implement change in your life

Change is either proactive or reactive. When the change is reactive and unwanted then one of the best frameworks I have seen for explaining the transition stages people experience is the Kuberler-Ross change curve. Reactive change requires resilience whereas proactive change requires courage. The focus of this article, however, is more about making proactive changes where the objective is how to implement change in your life and more specifically how to make positive changes in your life. The first step towards implementing change in your life is to ensure that you have an internal locus of control. This is where you believe that you, as opposed to external forces that are beyond your control, have control over the outcome of events in your life. An internal locus of control is achieved by an empowering mindset in which you understand that although you cannot control external events you know that you have the freedom to choose how to respond to them. You choose to be resilient and to have a positive attitude. You choose to make the best of your circumstances, to overcome obstacles, and to keep working towards what you want to achieve regardless of any setbacks that might come your way. You also know that nothing happens unless you make it happen, and to do that you need to put plans in place and take action.

Only two types of action count: Projects and Routines

When taking action there are only two categories that these actions can fall into. The first category of actions is continuous behaviour based on routines and habits. This is where subconscious automation plays a significant role in enabling you to get things done efficiently. If the change you are planning to implement in your life requires some sort of ongoing activity or behaviour change then you will need to plan, practice and embed a new routine to support this outcome. Routines are supported by habits and habits can be automated. James Clear’s book on Atomic Habits is one of the best resources I have read on the topic of habits. The reason you can ride a bike or drive a car without thinking about it is because that skill has been dynamically habit-stacked. Habit stacking is when a series of tasks are linked together in a specific sequence. This is a powerful way to establish new habits by adding and linking the new habits to existing habits. Dynamically habit stacking is where the related tasks are not constrained by a specific sequence but are dynamically interrelated to each other in such a way that the right combination can be applied in any situation when needed. Think of this in terms of more complex clustered skill sets like driving a car. There is always room for improvement, even when you know how to drive a car you can improve your mastery of this skill in new situations like learning to recover from a slide in a skid pan. Important routines that are continuously improved are forms of mastery. George Leonard’s book on Mastery is an excellent resource on this topic.

The second category of actions that will help you implement change in your life are time-limited actions associated with projects. Unlike continuous behaviour based on routines and habits, project-related activities are unique combinations of clustered actions that aim to achieve a specific outcome and when that outcome is achieved the project comes to an end. Projects have a well-defined start and end. Projects have a limited scope, although quite often part of the challenge of achieving a project is defining what that scope includes because every project I have ever worked on has required me to learn something new and until I realised what that was it wasn’t possible to include it in the scope of work for that project. Examples of projects are writing a book, building a new house, learning a new skill (like driving a car) and finding a new job.

Inevitably there is a grey transition area between these two categories of actions. There is a point where a project to learn a new skill (like meditation or playing the piano) transitions into a long-term mastery routine. There is also a hybrid between these two where you can use a project to define and establish a new routine. New routines and habits do not necessarily emerge by themselves, they need to be put in place and this focused objective is best achieved as a project. Attempting to change anything in your life automatically implies that something different needs to happen and that should always start as a personal project.

Semantics: Why not just set a goal?

Some people are goal-orientated and some are not. Some people are just trying to survive where they may be grappling with challenges associated with social anxiety, autism, some form of discrimination or economic inequality. If you are someone who feels that you can be motivated by goals, you’ll still find when you look at the goal more closely that it either entails establishing something new (a project), establishing a new habit or routine or changing an existing habit or routine. For those who are not into setting goals, the desire to make a change in their lives comes down to the same tools that the goal-setter uses: projects and routines.

Context is everything: an introduction to systems

Have you ever wondered why so many new year’s resolutions fail? It’s the same reason why so many people fail to achieve their goals. There are lots of statistics floating around on the internet that all point in the same direction and make the same point. Not everyone sets goals and for those who do a relatively small proportion of them actually achieve their goals. I’ve seen one assertion that only 8 per cent of people who set new year’s resolutions actually achieve them. In another article, the claim is that only 20 per cent of the population sets goals and of these only 30 per cent succeed. That works out to be about 6 per cent of the population, which is disappointingly low. But don’t get discouraged, there’s hope! Just about every article I have seen and book I have read on this topic falls into the same trap. Authors list very good reasons for why goals aren’t achieved and add value by suggestion a plethora of methods, hacks and tricks to focus on to ensure that you can achieve your goals, most of which would work if that was the weak link in your chain.

Each of these gurus, leaders, influencers, specialists, and consultants all have their favourite area of focus. Michael Hyatt, in his book Your Best Year Ever mentions doubt, mindset traps associated with the past, poorly defined goals, and a lack of sufficient motivation. Some proponents talk about ensuring that there are significant consequences as a way to address potential motivation challenges. If you were fortunate enough to attend Cliff Ravenscraft’s Free the Dream conference, you will have heard him talking about ensuring that the consequences of not achieving what you want to achieve must be so significant that it should threaten you with massive, overwhelming physical pain. So this approach leans into the carrot-and-stick principle where you can either reward yourself or suffer consequences. While reading Tim Ferriss’ book The 4-Hour Chef he mentioned the idea of using an anti-charity, which is a nonprofit that you would rather nuke than give money to, as a way to incentivise yourself to achieve your commitments. The idea is to place some money into escrow with a service provider like Stikk.com and if you don’t achieve your commitments then the money goes to your anti-charity. You can read about this in one of Tim’s blog posts. In one of Thomas Frank’s videos, he discussed how he used to schedule a Twitter tweet to go out just after his planned wake-up time (6:35 am) saying he was lazy so that this would incentivise him to get up and cancel the automated post actually going out. However, the universal principle of balance applies here and he discovered that there was an unintended consequence to this technique, specifically that he was waking up in the middle of the night with anxiety wondering whether he had missed the wake-up time or not heard his alarm and this was wrecking the quality of his sleep, so he made a change.

Systems perspective and problem types

However, these techniques only address the motivational aspect of the problem. I’m going to put on my engineering hat here and step back to make a really important point. It’s very easy to get caught up in the details of what other people think the reason may be for not achieving goals and trust me, there are many valid reasons with many potential solutions for each area of focus. Motivation is only one aspect of the problem. There is art and science in everything, and the art here is to work on the right problem. We all struggle to achieve goals for different reasons. The key is to identify what type of problem you may be struggling with. There are lots of different types of problems and understanding the nature of the problem will help guide your solution-seeking strategy. The deep insight here is to recognise that implementing change in your life is a systems problem. Unfortunately, systems problems are complex, but that doesn’t mean that they are insurmountable. The systems nature of problems associated with trying to implement change in your life means that you need to look at the full picture. There are internal and external reasons that might be holding you back.

Internal reasons may be things like:

- a lack of motivation

- the lack of a clear vision of success

- mindset blocks

- poor planning

- poor scheduling and ineffective time utilisation

- a lack of skills and, or

- limits to your relevant knowledge

External reasons may be things like:

- your environment doesn’t support you effectively

- the people in your immediate circle of influence aren’t supporting or enabling you

- your goal requires specific external events to happen

- you need the cooperation of others

- You may need some local or regional conditions to be met (e.g. travel or working visas)

- Specific global stability – economic prosperity, pandemic-free health environment that enables global travel, regions that are free of hostile conflict etc.

Some of these will be directly in your control and others will require you to work around things that you cannot control. You may need access to additional resources. Some of these things will take time to establish and may depend on how quickly you can find the relevant information, learn what you need to learn and find the resources you need to make the desired changes. You can work on your motivation by yourself. You can learn new skills by yourself, or find an app or a teacher to help you. You can work with someone to help you overcome a mindset block. You can teach yourself to improve your planning and scheduling skills. You can work on understanding human behaviour, and what motivates people and learn how to influence people to persuade others to help you achieve what you want to achieve. Some of this might take months or years of practice to master effectively enough to be able to use to support making the change you want to make. The bigger the system and the number of people involved the bigger the challenge. Anticipating and relying on how a group of people will respond to any changes you make is always going to be challenging. Some problems are more complex and challenging than others, so it’s important to choose your battles and more importantly, to carefully consider the size and scope of the magnitude of change you are trying to implement in your life. What you need is a complexity factor that you can benchmark your personal change objectives against that takes complexity and system dynamics into account.

The problem of probabilities

Some problems are dependent on probability distributions. If your goal is to start a business in a crowded market space your probability of securing a dominant market position is lower than if you entered a market that wasn’t already saturated. Finding employment as a medical practitioner without the relevant qualifications is highly unlikely too. Having some appreciation for the nature of the probabilities involved will help you use more discretion in selecting what aspect of your life you would like to implement change in. Some goals are simply more achievable than others. Part of the art of implementing change in your life is finding the sweet spot between too much of a stretch and not enough ambition in your goal objective. If the goal is too easy it may not inspire you enough and if it is too challenging it will probably demotivate you. The challenge must feel achievable. One of the most important mindset challenges to overcome is to move from not believing something is possible, to believing that it may just be possible. The art of a stretch goal is to turn a challenging objective into many smaller and more achievable little steps that when added together give you the bigger quantum jumps you are looking for.

Conclusion

There are essentially two types of change: external changes that force you to respond and internal changes in which you strive to achieve the desired outcome. External changes require you to be resilient, whereas internal changes require you to act with courage. When it comes to implementing change in your life you will need to act from an internal locus of control and be proactive. Some of the most impressive changes that occur in nature like the transformation of a caterpillar into a moth or butterfly teach us that significant changes are best achieved in a dedicated container (the chrysalis or cocoon). You can apply this principle by creating a dedicated space for change to occur in “The Delta Zone”, which when added to things that happen at work or in the rest of your life (work-life balance) establishes a third space or zone for things to happen. By separating change-related activities from the rest of your ‘normal’ activities and doing this deliberate and consciously you make change more tangible and manageable. Implementing change in your life requires you to take action and the two most powerful ways to do this are to use routines or to establish a project. Finding a new home to live in is a project. Once you’ve found it and moved in the change is complete and you can close the project. If you want to stay fit by running regularly, then you keep running. It becomes part of your daily or weekly routines. You might get ill and stop running for a while but when you get back to health you will start running again. There is no end to a routine. Both changes are permanent but the nature of the change is different. You can implement just about any change in your life through projects and routines.

The final consideration is that some changes are more challenging than others. The size and complexity of changes are sometimes influenced by probability and systems dynamics. Think of a system in terms of the environment around you and how everything in that environment has an influence over what you are trying to achieve. The most significant part of the system around you are the people you interact with and how their cooperation influences your ability to achieve the outcomes you are trying to implement. If you are looking for a new job you have to convince the recruiting manager that you’re the best person for that role. If you are looking for a new house, someone else needs to be selling theirs. If you want to live and work in a different country then you will also need to contend with rules and regulations, policies and procedures, macro and micro-economics, languages, cultures, socialised norms and expectations and a whole raft of other complexities, some of which may have a direct or indirect impact on your ability to implement the change you aspire to. The practical implication is that you need to access how achievable your desired change may be and figure out what needs to change and how that can be achieved. The size of the challenge needs to be in the ‘goldilocks zone’, not too big and not too small.

So in conclusion, you can implement change in your life with these three simple ideas:

- Separate the change you are trying to achieve into a dedicated change zone with its own ‘space’ and ‘time’ (the ‘Delta Zone’)

- Proactive change can be achieved by focussed action through projects or routines

- Changes are subject to system dynamics so the size and speed of the changes need to be carefully selected.